Imagine a time when women in India rarely stepped into science labs, let alone tackled the mysteries of the universe’s

most energetic particles. In the 1930s and 1940s, as the world grappled with cosmic rays—those invisible bullets from space racing toward Earth—one woman dared to dive in. Her name was Bibha Chowdhuri, often spelled Bhibha or Bibhabati.

She wasn’t chasing fame or headlines. She was driven by pure curiosity and an unshakeable belief in her own potential.

Bibha’s story isn’t just history; it’s a blueprint for anyone feeling overlooked, under-resourced, or out of place. She proves that real impact comes from persistence, not spotlights. This article uncovers her journey to motivate you: if Bibha could pioneer particle physics in a man’s world with limited tools, what can’t you achieve?

A Bold Beginning in Colonial India

Bibha Chowdhuri entered the world on July 3, 1913, in Calcutta (now Kolkata), a bustling hub of British India alive with

intellectual ferment. Born into a progressive Bengali zamindar family where her mother followed Brahmo Samaj principles supporting women’s education, she grew up in an era when girls’ education was a radical act. While many girls learned homemaking, Bibha devoured books on science. At Scottish Church College, one of India’s premier institutions,

she excelled in physics—this was no small feat as women were tokens in classrooms dominated by men. She earned her

bachelor’s degree, then pursued a master’s at the University of Calcutta, graduating in 1936 as the only woman in her class.

Physics wasn’t a “safe” choice; it was cutting-edge, blending math, experiment, and philosophy. Cosmic rays, discovered just decades earlier by Victor Hess, captivated her. These weren’t lab-made particles; they were nature’s accelerators, slamming into Earth’s atmosphere at near-light speeds, spawning showers of subatomic debris.

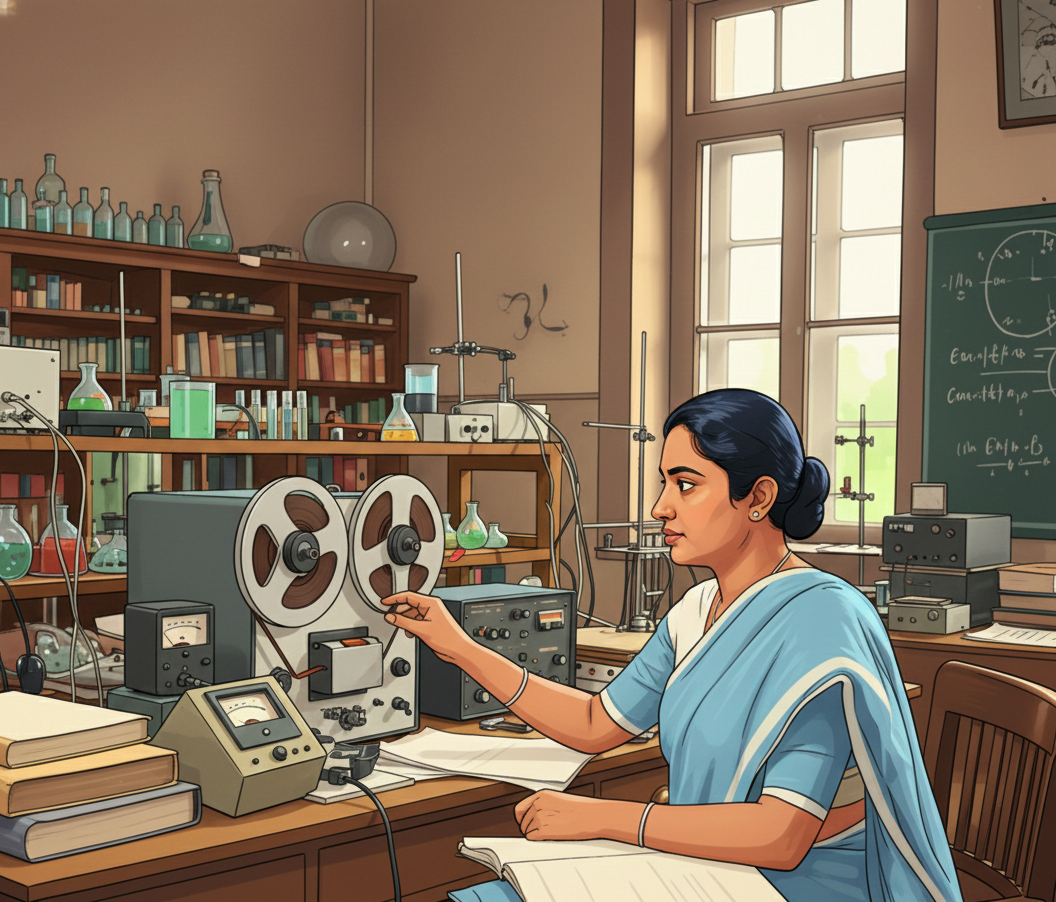

Bibha’s early spark came from lectures or textbooks on radioactivity, igniting a fire for experimental physics over theory

—hands-on work demanding precision in imperfect conditions. Picture a young woman in a sari, peering through cloud

chambers—glass boxes filled with vapor revealing particle paths as misty trails. No air-conditioned labs, no grants, just

grit. Her decision set her apart, motivating us today: chase what excites you, even if the path looks lonely.

Breaking Barriers at Bose Institute

By the late 1930s (~1936-39), Bibha joined the Bose Institute in Calcutta, founded by the legendary J.C. Bose—India’s mecca for physics, buzzing with ideas on quanta, waves, and the atom. Under mentors like D.M. Bose (Satyendra Nath Bose’s nephew), she plunged into cosmic-ray research. Why cosmic rays? Particle accelerators didn’t exist yet; these rays were free, ferocious natural colliders.

Her work focused on “showers”—cascades of particles from cosmic-ray collisions. Using photographic emulsions (special plates recording particle tracks like bullet holes in film), she measured track densities, lengths, and curvatures at high altitudes like Darjeeling and Sandakphu, revealing particle charges, masses, and energies. In key experiments, she studied penetrating showers, hinting at mesons—pions and muons— that later won Nobel Prizes for others.

Bibha’s days were grueling: exposing plates via balloons or mountains, developing them in dim darkrooms, analyzing under microscopes—hours counting “grains” along tracks. Her 1940s papers in Indian Journal of Physics and Nature

documented rare events like multiple meson production. Peers respected her rigor; she collaborated with international visitors, bridging Indian and global science. Challenges loomed: as a woman, she navigated skepticism—labs lacked facilities for women (no restrooms, no safe spaces), funding scarce post WWII. Yet she thrived, her results feeding global discoveries. Lesson: barriers build resilience. When doors half-close, squeeze through with excellence

Global Ventures and Unyielding Curiosity

Bibha didn’t stay insular. She earned her PhD from Manchester University in 1948 under P.M.S. Blackett (Nobel laureate), then worked at Ecole Polytechnique in Paris (1954-56), teaching French while using advanced cloud chambers in the Alps. These stints amid war and partition tensions sharpened her skills; she returned with techniques elevating Indian labs.

Back home, Homi Bhabha recruited her as the first woman at Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR, 1949-53), where she studied cosmic showers and K mesons, contributing to the particle zoo later unraveled at CERN. Post-independence (1947), India’s science boomed; she lectured, trained students, and ran experiments at Bose Institute into the 1950s-60s, later at Physical Research Laboratory (PRL) and Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics. No co-authorship glory, but her quiet input on “strange particles” (kaon precursors) mattered. Imagine decoding universe secrets with rudimentary tools. Her global exposure taught adaptability—importing knowledge, mentoring generations. Motivation: travel, learn, return stronger. It’s earned through hustle.

Trials of a Trailblazer: Facing the Odds

Bibha’s path was no fairy tale. India’s scientific ecosystem sidelined women—no fellowships targeted them; positions

went to men with family backing. She remained unmarried, channeling energy into science—a choice empowering yet

isolating. Socially, “spinster scientist” whispers stung. Resources? Emulsions cost dearly; altitude exposures risked

life (falls, weather). Data analysis manual, prone to error. Recognition? Her name faded beside giants like Bhabha or

Sarabhai—no Padma awards in her lifetime.

She persisted till her final 1990 paper, embodying stoicism: do the work, let results speak. Her underdog status mirrors

strivers today—first-gen students, women in tech, immigrants. She didn’t complain; innovated—reusing plates when funds dried, publishing when doubted. Pure motivation: obstacles aren’t stop signs; they’re tests

Rediscovering a Hidden Hero

Bibha faded from textbooks, but revival began in the 2010s. Historians and journalists spotlighted her via The Wire, The Better India. In 2018, Google Doodle honored her on National Science Day; Vigyan Prasar profiled her; calls grew for a Bibha Chowdhuri Fellowship. Diversity pushes unearthed her alongside Marie Curie, Lise Meitner—women physics shaped but history dimmed. In India, amid Chandrayaan triumphs, she reminds: roots run deep, often female and forgotten. Her legacy? Bose Institute halls echo her; students invoke her name. Star HD 86081 “Bibha” (IAU-named 2019 in Sextans constellation) shines eternally. She normalized women in labs, paving paths for later pioneers

Lessons to Fuel Your Fire

Bibha’s life screams motivation. Choose the hard path: Physics in 1930s India? Insane for a woman. Yet she picked

passion over ease. Persist through invisibility: No fame chased her, but impact endures—active till 1991 death on

June 2. Adapt and collaborate: Calcutta to Manchester/Paris, she evolved. Defy stats: <1% women in physics then—be the exception. Legacy over likes: Inspires millions now

Why Bibha Chowdhuri Matters in 2025

Today, with AI tools and online courses, excuses shrink. Bibha Chowdhuri had none—no Google, no funding portals—yet pioneered. For your audience—”people” hungry for hope—she’s proof: ordinary origins birth extraordinary lives.

Parents, tell daughters: Bibha Chowdhuri started like you. Students, crushed by rejection? She faced worse. Professionals stalled? Her persistence won. India’s space-nuclear feats trace to her era. Honor her: read her

papers (digitized online), visit Bose Institute, share her story.

A Call to Rise Like Bibha

Bibha Chowdhuri wasn’t superhuman. She was determined, curious, resilient. In a world screaming “impossible,” she

whispered “watch me.” Her tracks—etched in emulsions, now in history—urge you: track your own showers of success.

What’s your cosmic ray? Chase it. Persist. Inspire. Bibha Chowdhuri did; now you.