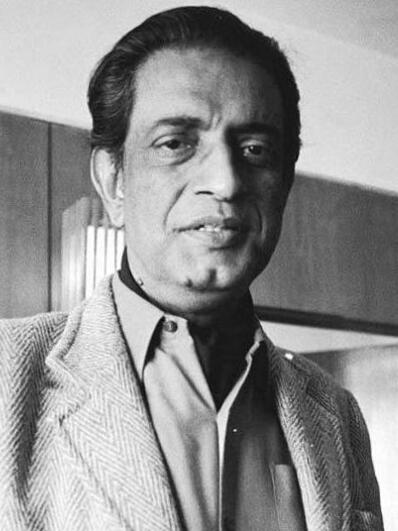

In an era when Indian cinema was dominated by song-dance spectacles and melodrama, one quiet, bespectacled man from Kolkata picked up a camera and chose something radically simple: truth. Satyajit Ray did not set out to become a global icon. He wanted to tell honest stories about ordinary people. Yet his films changed how the world looked at India and how India looked at itself.

Satyajit Ray ‘s journey is not just about cinema; it is about courage, craft, and character. He faced money problems, skepticism, censorship, and health crises. Still, he kept making films on his own terms. For anyone who feels that talent plus integrity cannot survive in a harsh world, Ray’s life quietly replies: it can.

Roots in Bengal: A Childhood of Creativity

Satyajit Ray was born on 2 May 1921 in Calcutta (now Kolkata), into a distinguished Bengali family of writers and artists.

His grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, was a pioneering printer, publisher, and children’s author. His father,

Sukumar Ray, was a brilliant humorist and nonsense poet whose work is still beloved in Bengali households. Satyajit Ray lost his father when he was very young, and the family struggled financially, but his home was rich in books, art, and ideas.

He studied at Ballygunge Government High School and then at Presidency College, Calcutta, where he completed a degree in economics but spent much of his time reading, drawing, and watching films. After college, he joined Rabindranath Tagore’s Viswa-Bharati University at Santiniketan, where he was exposed to Indian classical art, sculpture, and music, and also to Eastern and Western aesthetics. This deep artistic grounding later shaped his uniquely balanced style—modern yet rooted, simple yet profound

From Advertising to Film: Learning to See

Satyajit Ray did not jump straight into filmmaking. He first worked as a commercial artist at D.J. Keymer, a British advertising agency in Calcutta. There he learned layout, typography, and visual communication skills he later used to design his own film posters and credit sequences. In the evenings he joined the Calcutta Film Society, which he co-founded in 1947. Through this, he and his friends screened and discussed the best of world cinema from directors like Renoir, De Sica, and Eisenstein.

In 1949, French director Jean Renoir came to India to shoot The River. Satyajit Ray helped him scout locations, observing closely how a major director worked with light, landscape, and actors. A year later, Satyjit Ray travelled to London for his advertising job and watched around 100 films in six months. One of them Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves—made a huge impact. Its simple, neorealist story of a poor man and his stolen bicycle convinced Ray that such truthful, small-scale cinema was possible in India too.

This phase is important for anyone chasing a dream: Satyajit Ray didn’t wait for perfect conditions. He learned wherever he was at an ad firm, in film societies, on foreign trips—and slowly assembled the skills and confidence he needed.

The Birth of Pather Panchali: Courage on a Shoestring

Satyajit Ray’s first film, Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road), based on a novel by Bibhuti bhushan Bandyopadhyay, began as a passion project. He wanted to show rural Bengal not as a postcard but as a living, breathing world its beauty, poverty, and quiet dignity. However, money was a huge obstacle. Producers were skeptical: no stars, no songs, no clear “commercial” formula

Satyajit Ray started the project in 1952 with a mostly amateur crew, including cinematographer Subrata Mitra and art director Bansi Chandragupta, who would later become legends. Funds kept running out. At one point, Satyajit Ray used his own savings and even his wife’s jewelry to keep the shoot going. Shooting stretched over nearly three years. There were doubts from everyone except Ray and his close team.

Finally completed in 1955, Pather Panchali premiered in Kolkata to mixed commercial response but strong critical

admiration. Then it went to the Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Best Human Document award. Suddenly, the

world took notice. A low-budget Bengali film about a poor village boy and his family had broken through global barriers.

For every creator who feels blocked by lack of funding or resources, the story of Pather Panchali offers a powerful

reminder: belief, persistence, and craft can turn a “risky” idea into a classic.

The Apu Trilogy: Growing Up on Screen

Satyajit Ray followed Pather Panchali with Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956) and Apur Sansar (The World of Apu,

1959), forming the famous Apu Trilogy. Across these three films, the audience watches Apu grow from a curious child in a village to a thoughtful young man in the city, facing loss, love, ambition, and responsibility.

Aparajito shows Apu’s move to the city and his education, as well as his mother’s loneliness and death.- Apur Sansar presents Apu’s unexpected marriage, deep love, tragic loss of his wife, and eventual reconciliation with his son.

These films are deeply human, not just “Indian” or “Bengali”. Critics around the world praised their emotional honesty, visual poetry, and nuanced performances. For young people, Apu’s journey mirrors many modern struggles: leaving home, balancing dreams with duty, surviving grief, and learning to grow up without losing sensitivity.

A Complete Storyteller: Director, Writer, Composer, Designer

Unlike many filmmakers who focus on only one aspect of cinema, Satyajit Ray was a complete creative powerhouse. He Wrote or adapted most of his screenplays himself. Designed posters, title cards, and often storyboards. Directed actors with a gentle, precise hand often using non professionals. Composed music for many of his later films, especially from Teen Kanya onwards.

Satyajit Ray also wrote prolifically in Bengali. He created iconic fictional characters like the detective Feluda and the eccentric scientist Professor Shonku, whose stories have inspired generations of young readers. His Feluda tales, like Sonar Kella and Joi Baba Felunath, were later adapted into beloved films he himself directed.

This multi talented approach shows an important lesson: developing skills across different areas can strengthen your

main craft. Satyajit Ray’s understanding of design, music, and writing made his films richer and more unified.

Beyond Apu: Social Critique and Psychological Depth

Although the Apu Trilogy made him famous, Satyajit Ray’s later work explored a wide range of themes and genres.

Charulata (1964): A sensitive portrait of a lonely, intelligent woman in a 19th-century Bengali household, based

on a Tagore story. Satyajit Ray later said this was his personal favorite among his films.

Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963): The story of a housewife who takes up a job in Kolkata and discovers independence,

tackling gender roles and middle-class anxiety.

Seemabaddha (Company Limited, 1971) and Pratidwandi (The Adversary, 1970): Sharp critiques of corporate ambition and urban unemployment.

Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder, 1973): On the Bengal famine of 1943, highlighting how ordinary villagers suffered

during historical crises.

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) and its sequels: Fantasy musicals for children and adults, mixing humor, politics, and

imagination. Together, these films show that Satyajit Ray did not repeat himself. He constantly observed changes in Indian society urbanization, consumerism, political unrest and responded with stories that were subtle but powerful. For a modern creator, Satyajit Ray’s example is invaluable: stay curious about your surroundings; let your work grow as the world changes.

International Recognition and the Oscar

By the 1960s and 1970s, Satyajit Ray had become a major name in world cinema. Critics compared him to directors

like Akira Kurosawa, Ingmar Bergman, and Federico Fellini. Kurosawa famously remarked that not seeing the cinema of

Satyajit Ray meant “existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon” Satyajit Ray’s films won numerous awards at international festivals: Venice, Berlin, Cannes, and others.

In India, he received the Dadasaheb Phalke Award (the highest honor in Indian cinema) in 1984 and later the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian award, in 1992. In 1992, seriously ill and hospitalized in Kolkata, Ray received an Honorary Academy Award (Oscar) for his lifetime achievements in cinema. The award was presented to him via

video link, and his brief acceptance speech, delivered from his hospital bed, moved audiences worldwide. He died shortly afterward, on 23 April 1992.

His life offers a powerful message: even if you begin far from the centers of global power, deep, honest work can still reach the world.

Working Style: Discipline, Simplicity, and Respect

Those who worked with Satyajit Ray often mention his calm, disciplined presence on set. He prepared thoroughly, often drawing detailed storyboards and planning each shot well in advance. Yet he allowed room for natural performances and small improvisations. He treated actors whether famous or new with respect, explaining the emotions and motivations behind every scene.

Satyajit Ray preferred natural light when possible, simple camera movements, and clean editing. His films are not flashy, but they are visually precise and emotionally clear. This unshowy style teaches an important creative principle: technique should serve the story, not distract from it

Satyajit Ray the Writer: Inspiring Young Minds

Satyajit Ray’s literary work, especially in Bengali, has inspired countless children and teenagers. The Feluda detective stories, for instance, feature a sharp-minded sleuth, his cousin Topshe, and writer-friend Jatayu, combining mystery with travel, humor, and cultural insight. Professor Shonku stories bring science, adventure, and imagination together, encouraging curiosity about technology and the unknown. For readers, especially young ones, Satyajit Ray becomes more than a director; he is a mentor through stories. His writing style clear, engaging, with moral depth but no preaching shows that serious ideas can be communicated with simplicity.

Health Problems and Unfinished Dreams

In the 1980s, Ray’s health began to decline, including heart issues that limited his activity. Even then, he continued to

write, plan, and direct films like Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World, 1984), Ganashatru (Enemy of the People, 1989),

and Agantuk (The Stranger, 1991). These late films often revolve around questions of morality, truth, and the clash

between modern values and traditional beliefs.

He left behind some unrealized projects and many ideas, but by the time of his death, his body of work around 36 films, plus books, essays, and designs had already secured his legacy. His life reminds us that even with illness and aging,

sustained commitment to one’s craft can produce meaningful work.

Lessons from Satyajit Ray’s Life

Satyajit Ray’s story carries several powerful lessons Start where you are: Satyajit Ray began in advertising, film

societies, and small creative circles. You don’t need perfect conditions to begin. Learn from everywhere: He used travel, books, painting, music, and conversations as fuel for his cinema. Stay true to your values: He refused to compromise on artistic integrity even when commercial pressures were strong.

Respect your audience: Satyajit Ray believed viewers could handle subtlety and complexity; he never “dumbed down” his films. Keep evolving: From rural stories to urban critiques, from children’s fantasy to political drama, he kept expanding his range. Let your work speak: He did not rely on publicity or controversy; his films and writing built his reputation over time.

Why Satyajit Ray Still Matters Today

In a world of fast content and viral trends, Satyajit Ray’s life and work offer an alternative model of success. He shows that Depth can outlast hype. Authentic local stories can move global audiences. Art and ethics can coexist. A single dedicated person can elevate the reputation of an entire industry and culture.

For filmmakers, writers, students, and dreamers, Satyajit Ray’s journey is a reminder that vision plus discipline can build

something timeless, even from modest beginnings in a corner of Kolkata.